Exhibition information

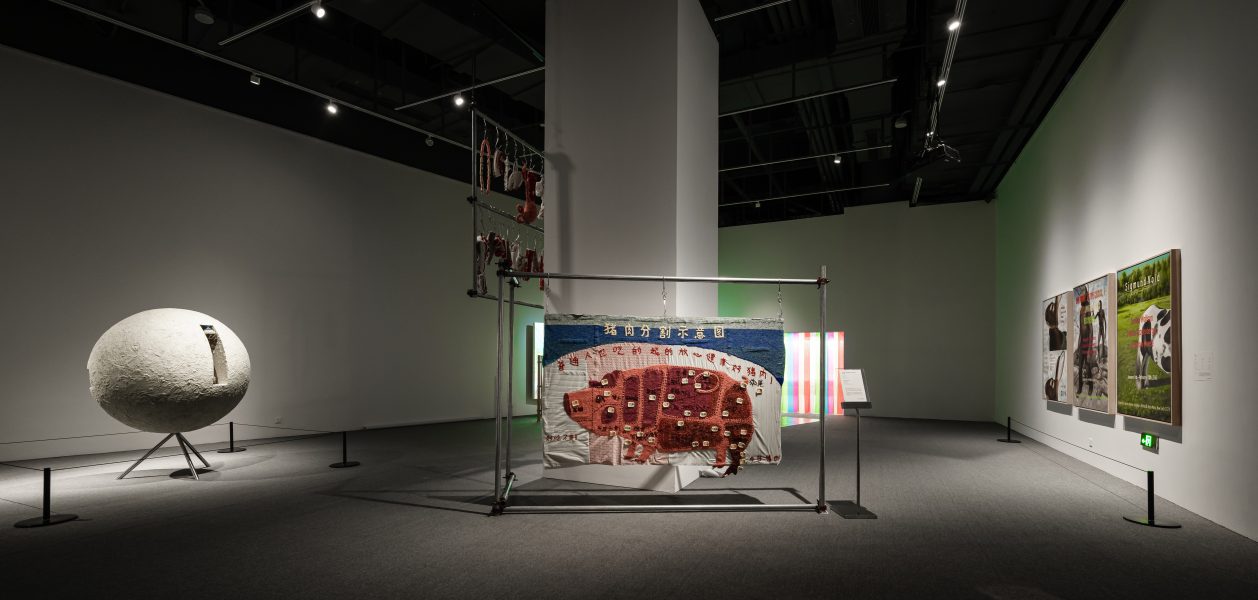

Deji Art Museum organizes the group exhibition Nián Nián :The Power and Agency of Animal Forms, featuring 59 works by 33 Chinese and international artists. In light of the challenging reality shared by the human community over the last three years, the theme of the exhibition nurtures the powers of introspection, healing, and renewal.

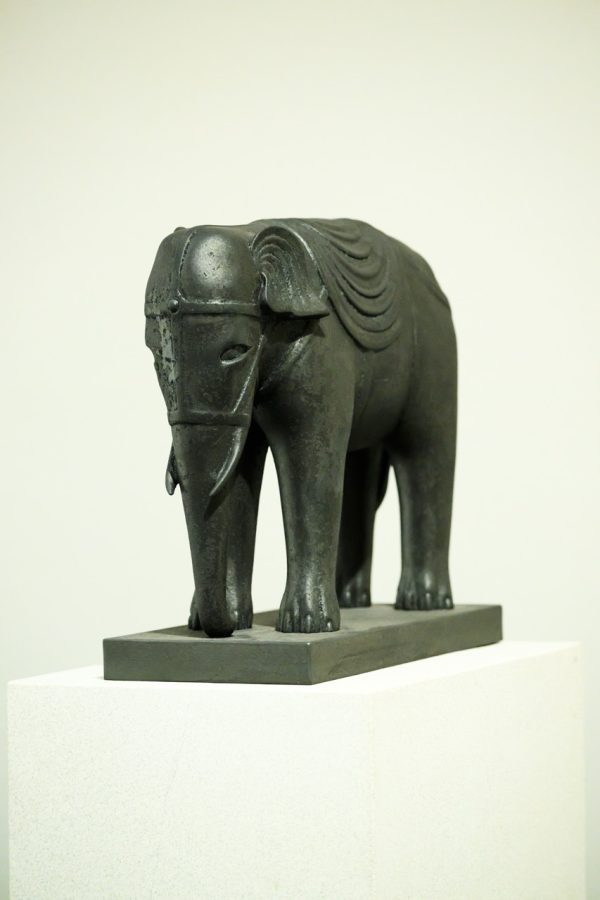

This exhibition draws on Deji Art Museum’s long-standing research centered around localism and contemporaneity. Serving as a geographic backdrop in human-animal relations, Nanjing is the cradle of modern geological and paleontological research in China. It boasts the largest institution in China to host the most comprehensive range of paleontological and stratigraphic research. The ancient capital is also preserving creative lineages of animal forms throughout the lineage of Chinese civilization. The Hongshan Forest Zoo in Nanjing is the first-ever institution in China to declare, and protect animal rights. Furthermore, the exhibition continues to explore the philosophical and practical relationships between art and technology initiated in An Era in Jinling and In the Line of Flight, for Possible Worlds after the recent reopening of Deji Art Museum. The exhibition aims to relate and understand the creation and expression of animal imagery in contemporary art within the triadic relationship between humans, animal/nature, and technology.

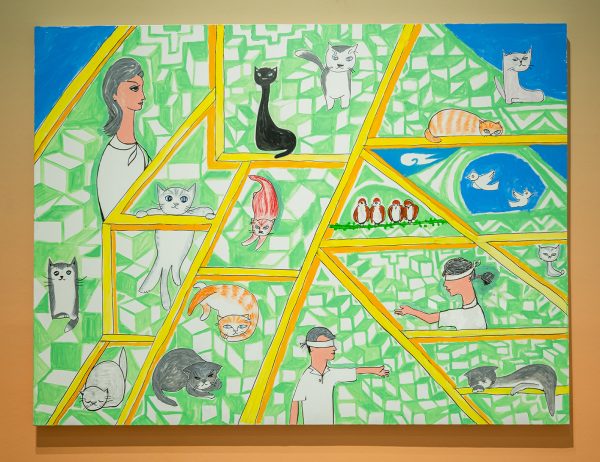

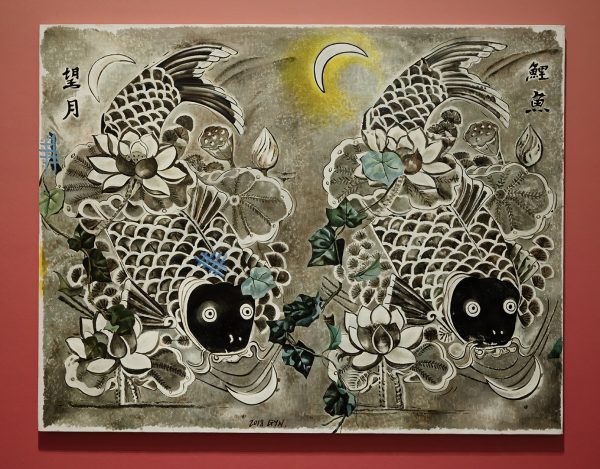

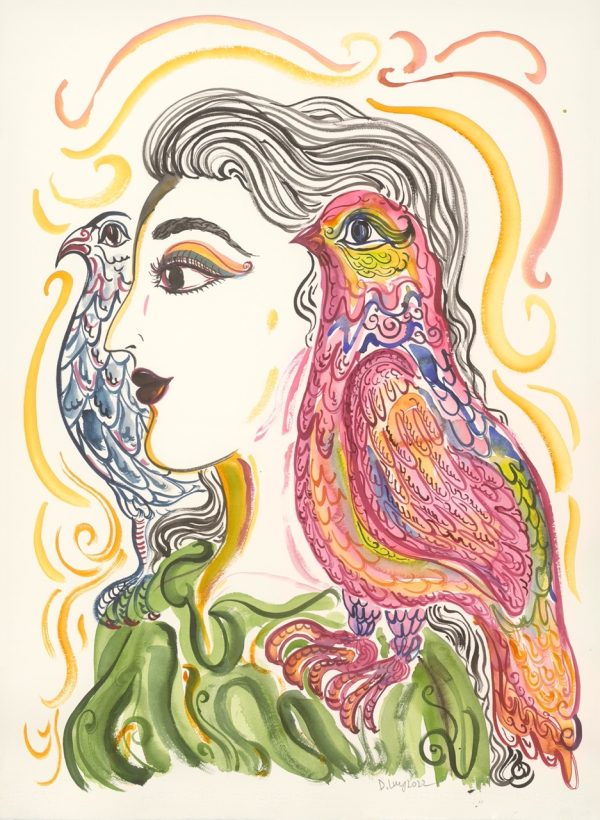

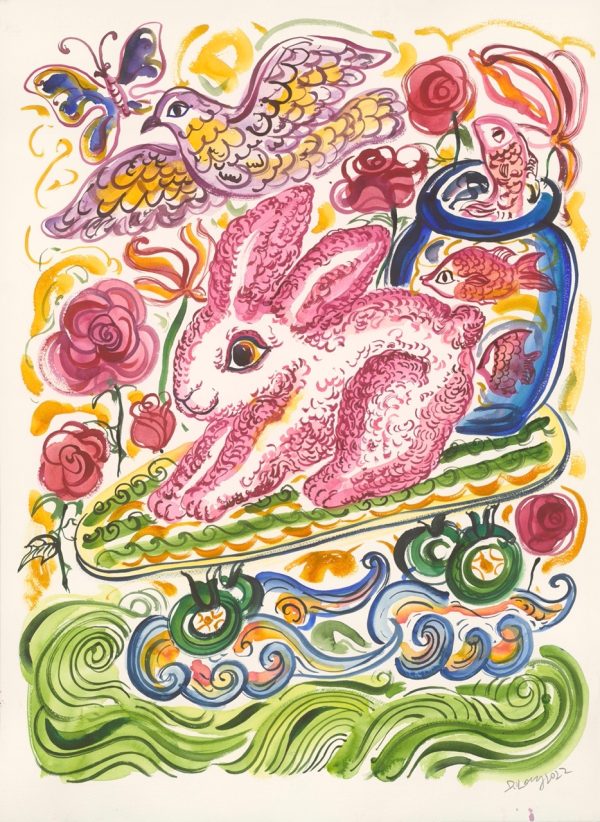

Nián Nián :The Power and Agency of Animal Forms showcases a large number of figurative animal images embedded in contemporary art (both Chinese and international). Animal themes have an early origin in the history of images. In facing harsh and uncontrollable natural environments, our ancestors placed their spirits upon animals for safekeeping, and animal totem images and totem worship have since emerged. In the present day, the “skins” of virtual animals digitally generated by rendering technology, with their abstract, precise, and highly controlled appearance, form a linguistic style seemingly opposed to creativity that spontaneously chases inspirations. These two ways of producing appear divergent, but their goals are surprisingly unified: to reveal the energies of the natural world while refining the methods of image making.

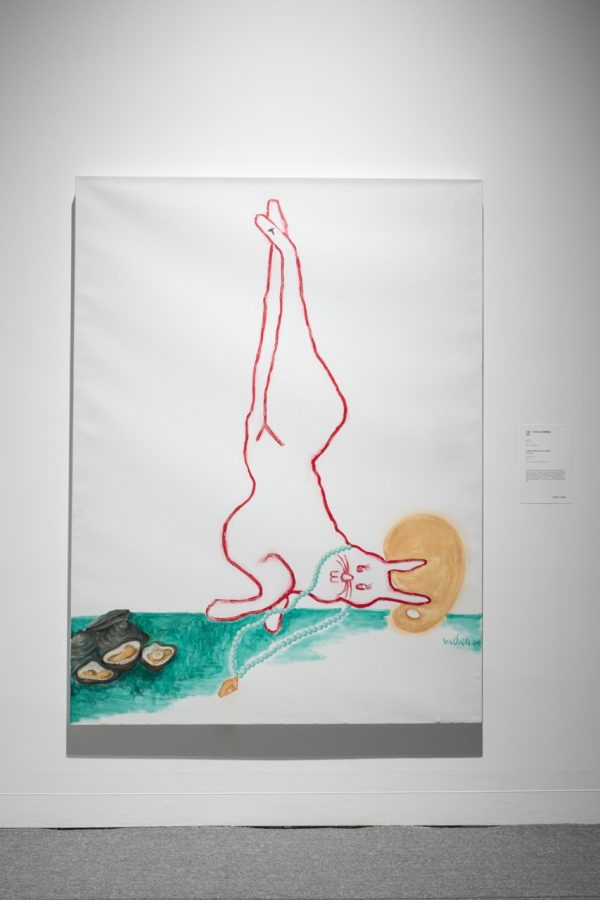

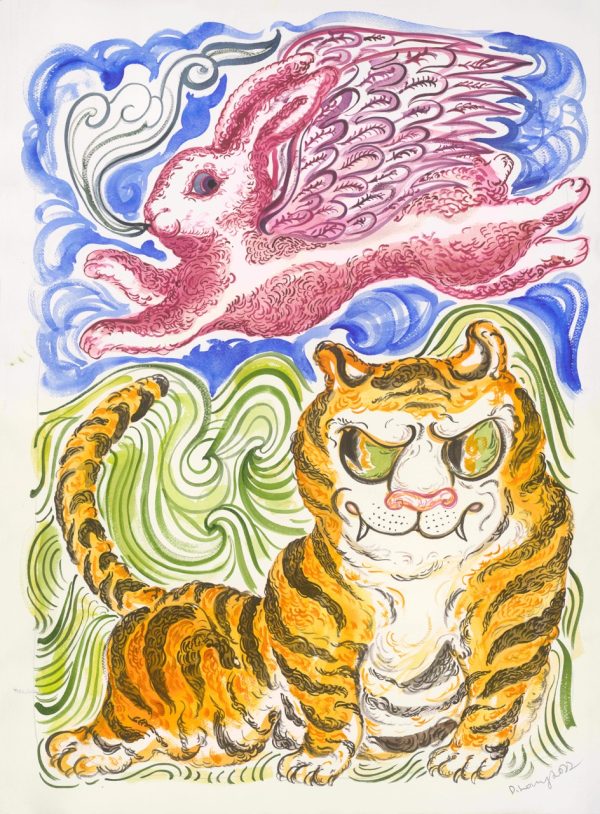

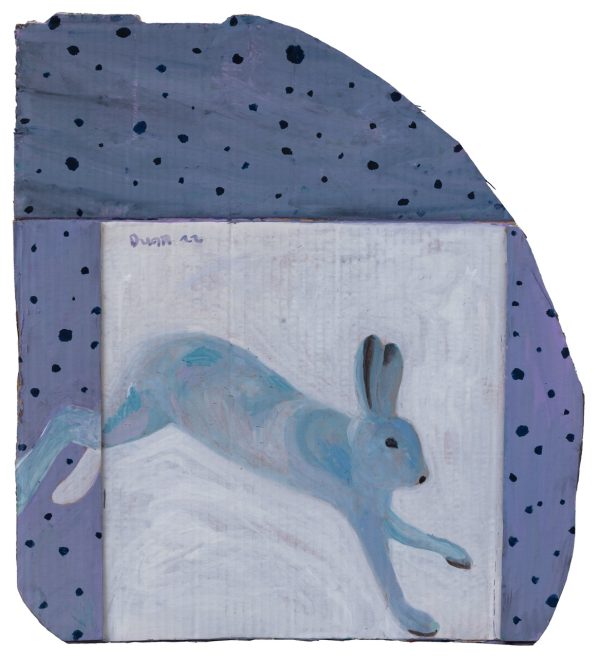

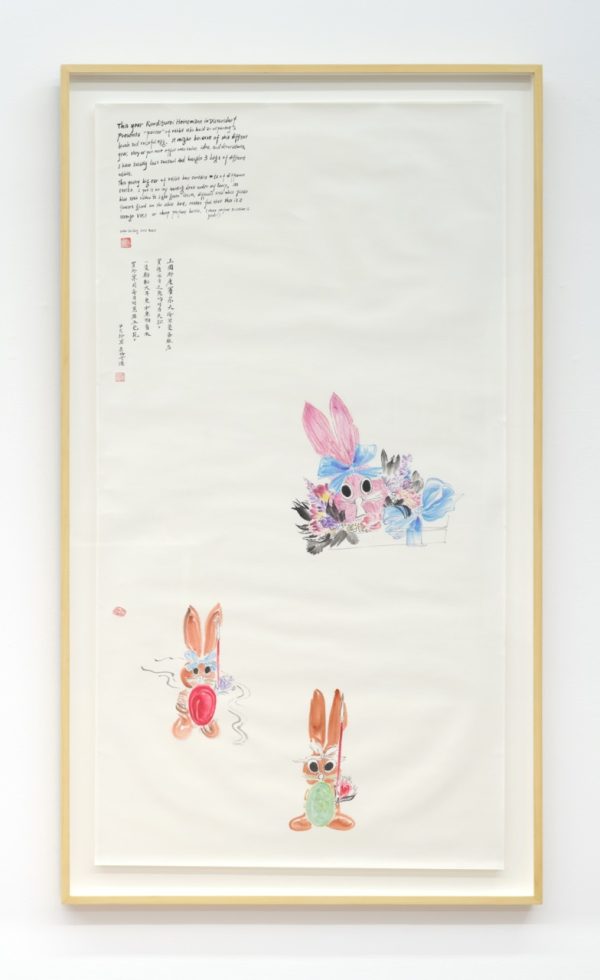

While the exhibition attempts to re-familiar the viewers’ with the enduring “animal” motifs, it also unfolds the evolutionary trajectory of the ways contemporary artists observe the world gently or radically. In the coming Year of the Rabbit, may the exhibition unravel fresh horizons and “stimulate new erudition in old learning.” In the hopes and wishes bestowed by animal forms in the new year, may we be free!

Curatorial Essay

The great Heinrich Wölfflin (1864-1945, born in Zurich) stated in his Principles of Art History that linear depiction “presents things as they are” and painterly depiction “bases its representation on that image in which visibility really appears to the eye.” Perhaps sounding a bit general and vague even to himself, he has explained his point of view. From the Renaissance to the Impressionists, he cites a vast number of examples to show that linear depiction is a solid, tangible grasping of the object depicted, rich in tactile sensations.¹ The painterly, however, leaves only an optical appearance, a flat layer that is reserved for the eye. This is not difficult to understand. This pair of concepts is not well known to us, probably because of the cultural differences in translation between East and West — We often understand the term “linear depiction” simply as a modeling technique using outlines in Chinese painting. For Wölfflin, the use of contour lines is not the difference between linear and painterly works.² Both approaches (which, according to him, are not limited to personal reasons, but are also the result of national and contemporary production) are influenced by the way the world is observed. As an apple, an animal, or a large living person becomes an artistic subject, whether it is ultimately solid and stable or composed of a patch of colorful light, is decisive in art.

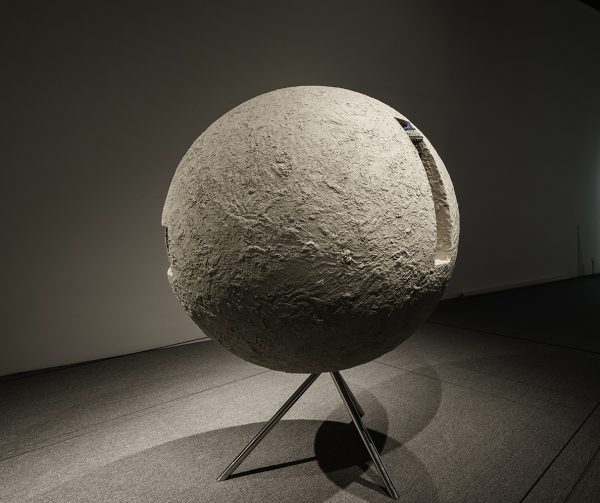

One of the initial reasons for curating “Nián Nián” is to discover the transformation of this kind of artistic style division in the present. Let us call the new style “epidermalization.” When playing The Sims 4 on the computer or The Legend of Zelda on the Nintendo Switch console, one always encounters the occasional awkward moment when the player’s gaze momentarily penetrates the skin of a game’s protagonist and peers into the emptiness of his or her body. Those characters that repeatedly resonate with the player’s inner psyche, seemingly flesh and blood, turn out to be just simple layers of skin. The German philosopher Peter Sloterdijk proposed a theory of microspherology, the hypothesis that we live in imaginative constructs of “bubbles” (Blasen) in the world. The aforementioned modeled and rendered images provide another layer of novel interpretation: We do not live inside the bubbles; all we see are bubbles — skins that are theoretically infinitely close to zero in thickness and are “representing things according to virtual spatial relations.” They are not tactile and they are not optical. They are abstract, precise, highly controllable, inaccessible and irrefutable to the viewer.

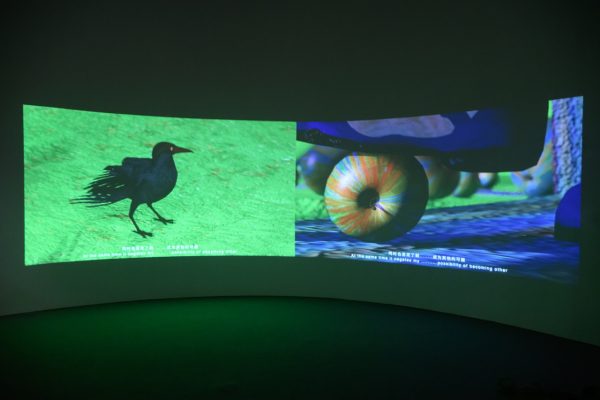

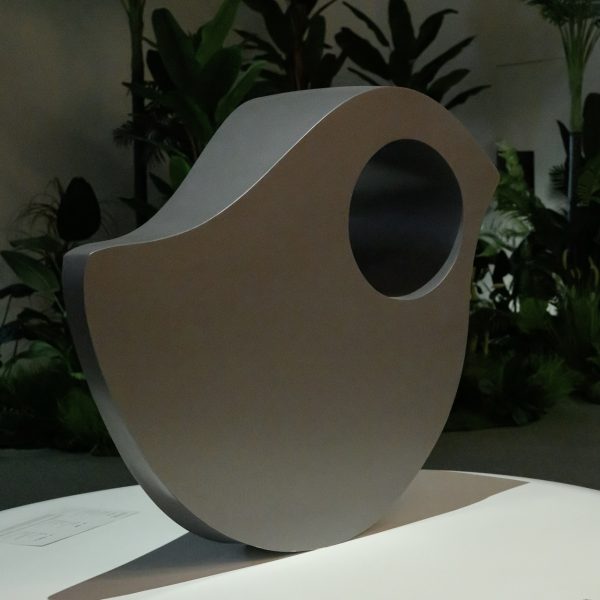

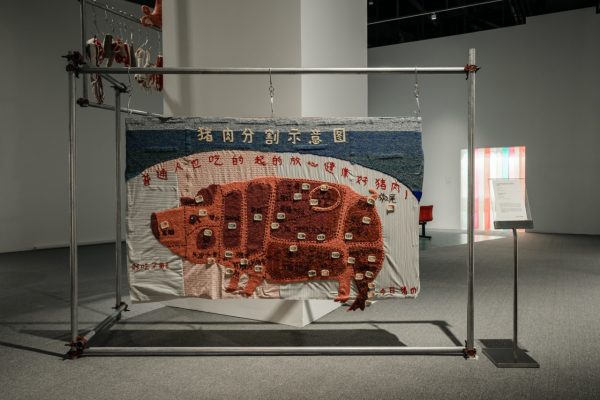

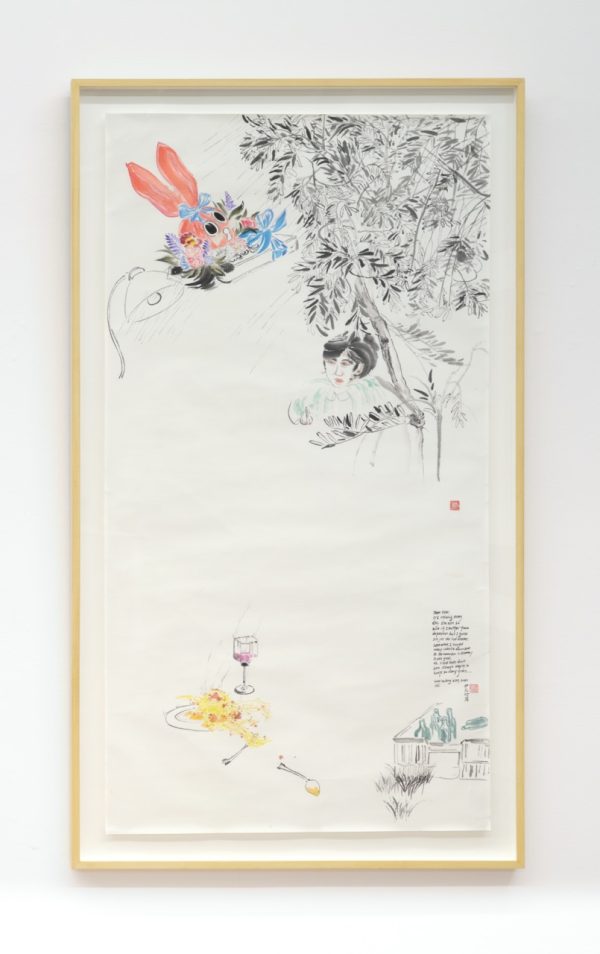

Nowadays, when discussing art and technology, technology is often seen as a consensus and a belief, and art is deployed as a ritual means of establishing this belief. In “Nián Nián”, the task of reifying ideology and gaining widespread recognition is assigned to the image of animals. As far back as the animal wall paintings in the Lascaux caves in France, the subject of animals has been present in the history of images. As for right now, the Chinese New Year is fast approaching, and the beast Nián (meaning “year”) as well as the twelve Chinese zodiac signs are all animals exuding lively, festive, and warm qualities. Such themes naturally transcend cultures and media — from the traditional to the virtual and superficial.³ The exhibition includes paintings, sculptures, and videos with smooth surfaces, like a succession of “bubbles.” These include Sun Yitian’s shimmering balloon-like painting Two Headed Dragon, Shen Xin’s citation of Faceshift’s image of the Shan Hai Jing as the embodiment of a debater on the topic of neoliberalism (Shoulders of Giants), and even Tong Tianqing’s traditional paper lanterns made of sorghum stalks, Guimao(The Year of the Water Rabbit)Lantern, to name a few. The work closest to articulating Sloterdijk’s theory is Tang Chao’s Mind Movie: A Horror Story. Using a narrative montage constructed with the modeling and split-screening software Previs Pro, Tang creates a tribute to Tsui Hark’s Love in the Time of Twilight, responding to the hundreds of lives trapped in the iterative information media of video tubes, beta tapes and virtual reality.

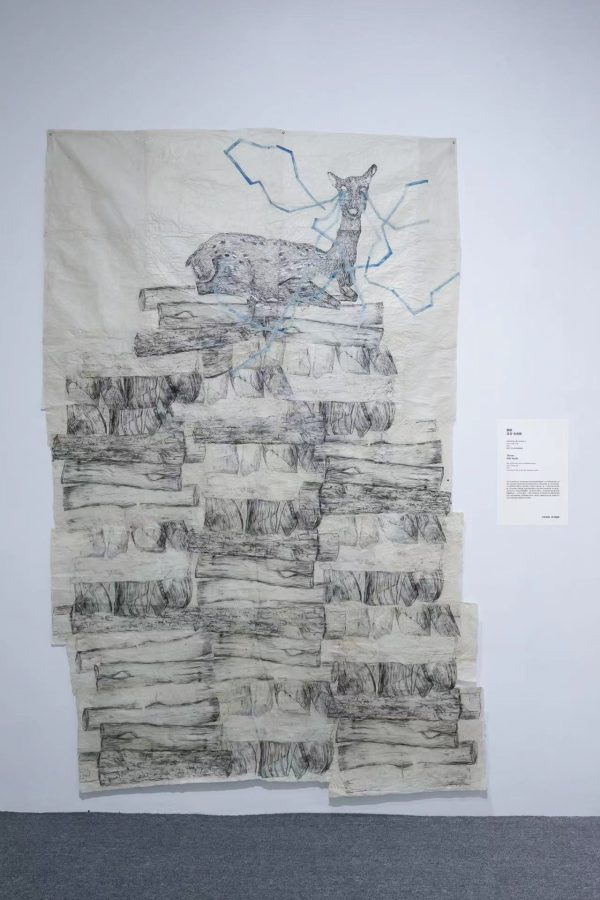

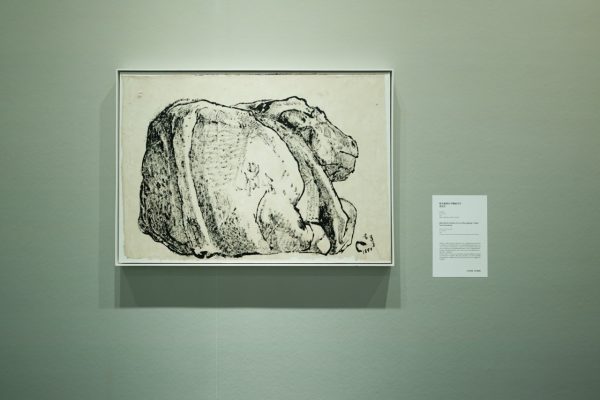

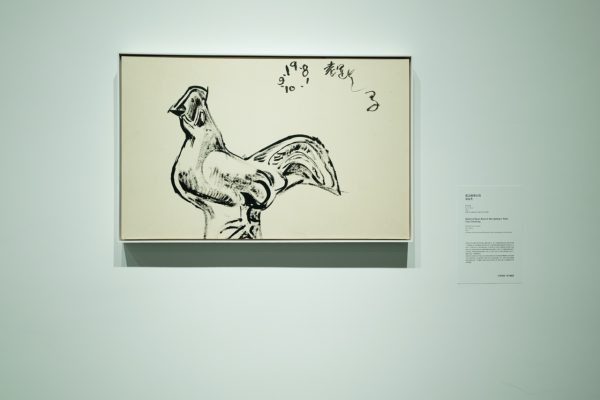

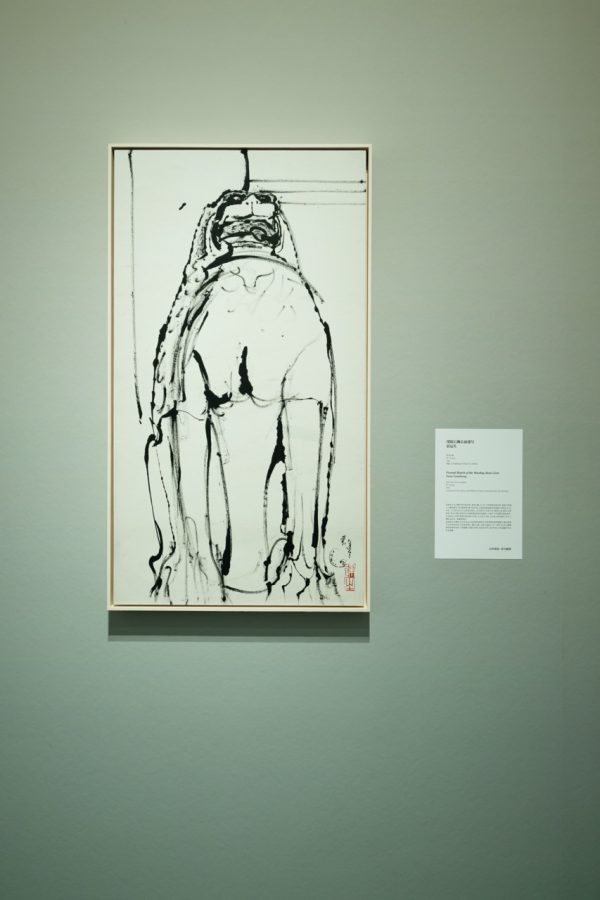

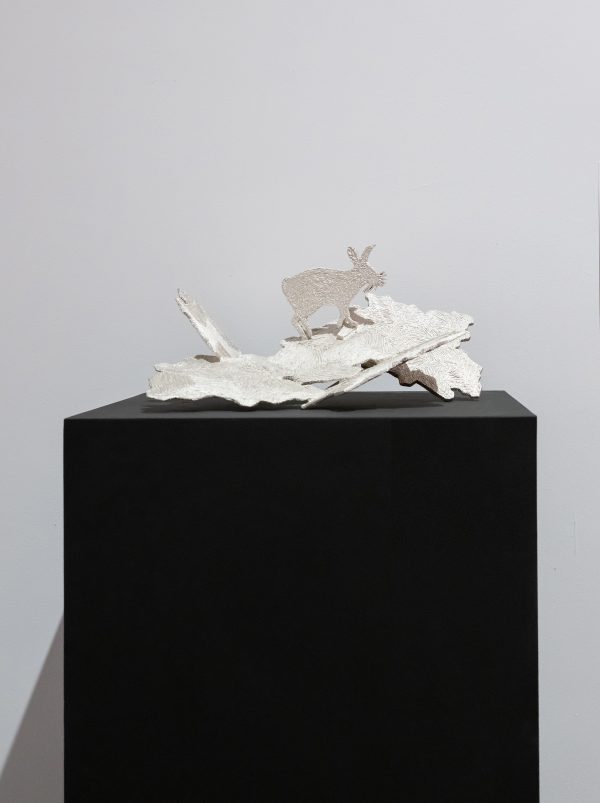

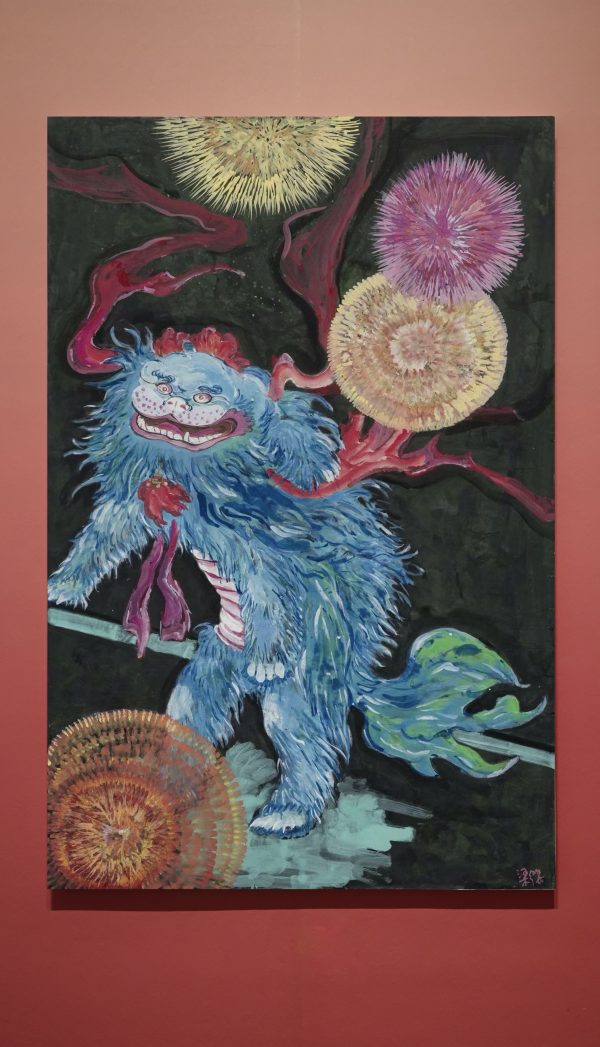

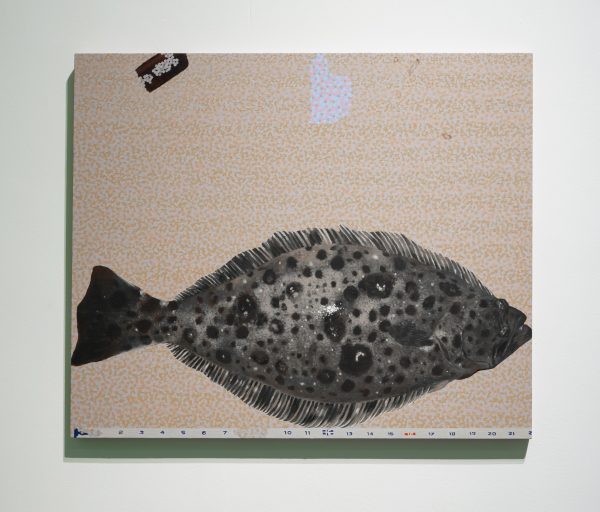

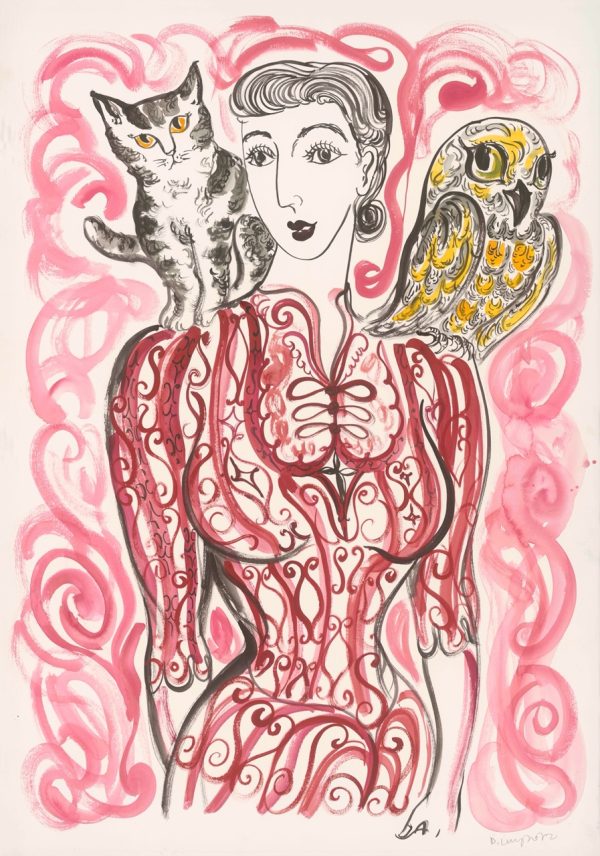

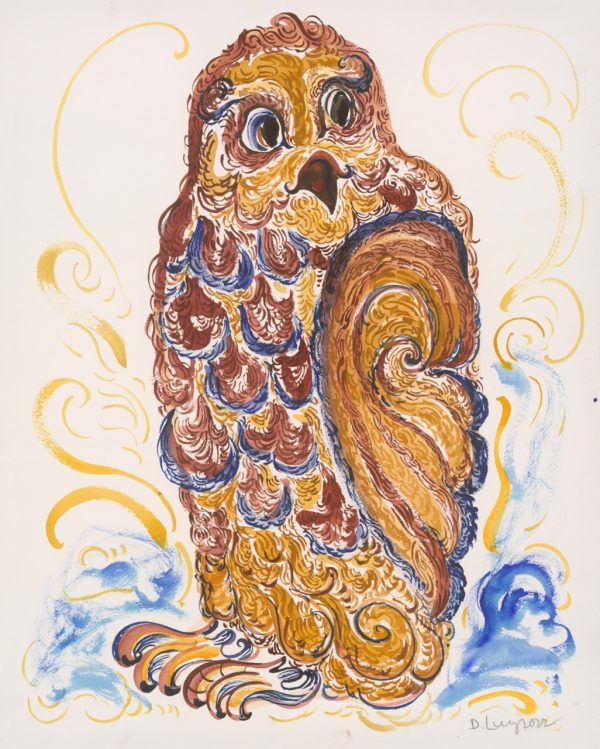

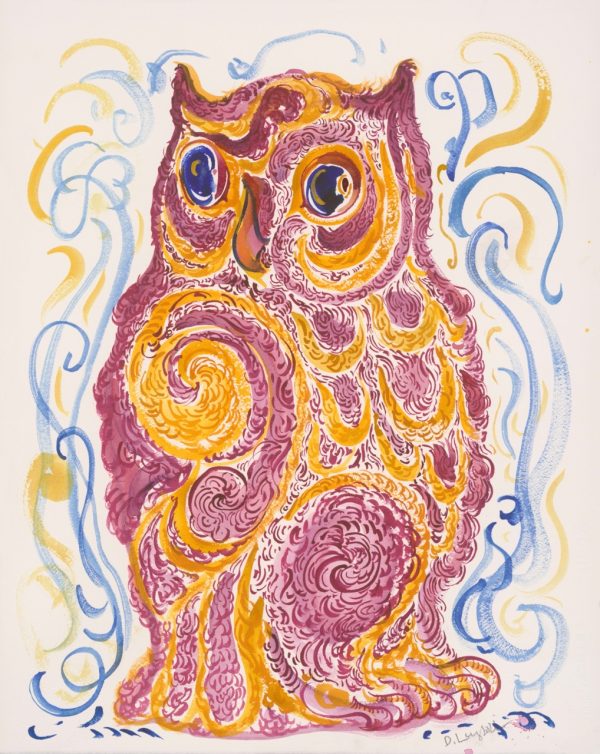

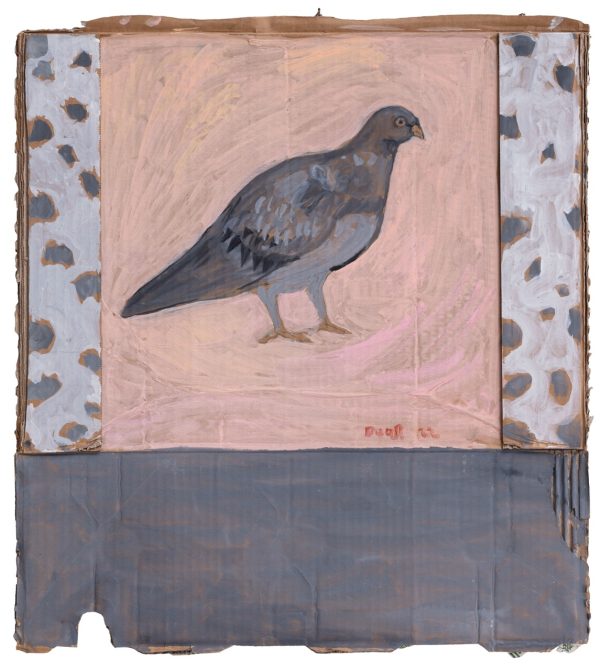

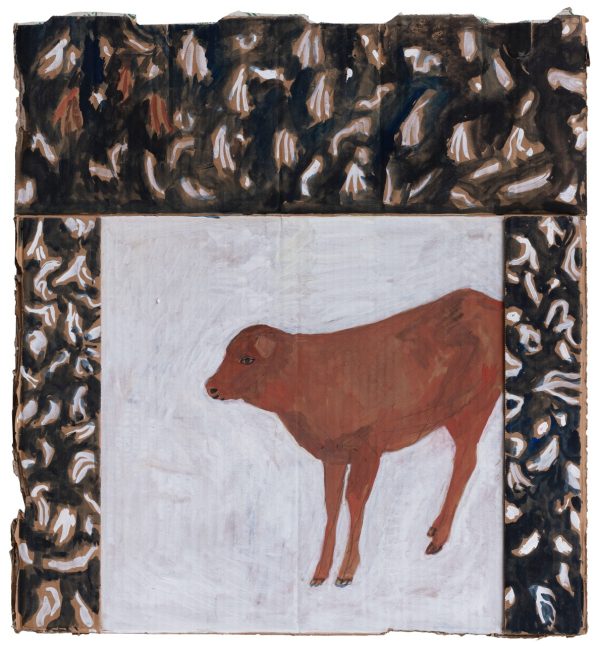

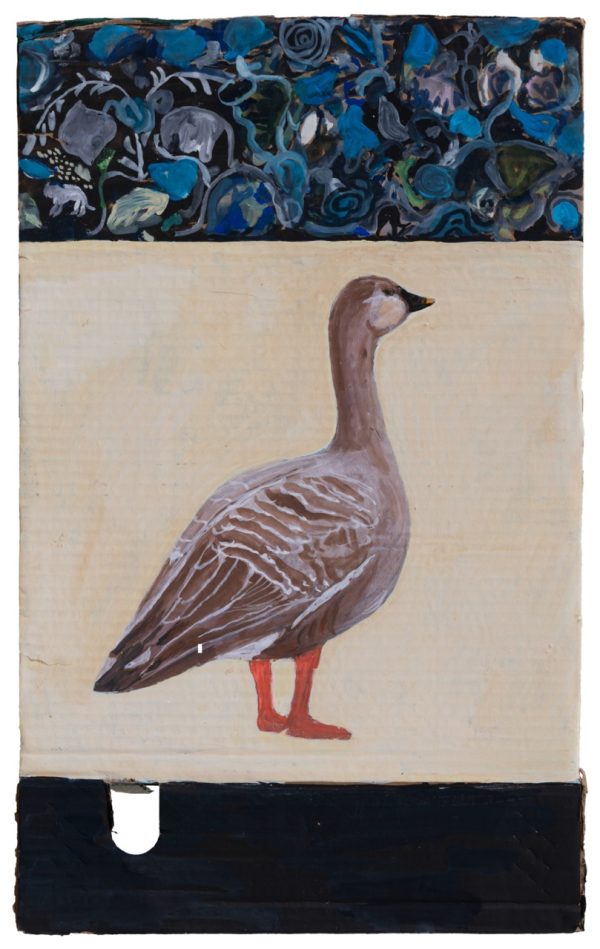

In contrast to “skins,” the other category of works included in “Nián Nián” directly expresses a sense of spirituality, endowing the textures of creation with indescribable richness. The artist’s intuition, the accumulation of emotions and “touch,” invites elements of chance to the creative process. The athletic brushstrokes of Liang Ying’s lion dance (Jing Shi), the rustling lines of Kiki Smith’s fallow deer (Throne), and David Shrigley’s relaxed attitude and effortless approach toward animals of all kinds (Animals) unfurl an unambiguous suggestiveness, forcing the viewer to notice the vigor and energy that flows from within. The creators of the “skins” in the exhibition invoke stiff models and subtly inject life into them from the outside. If these industrialized and virtual products are called “linear depictions,” it is the conviction of the creators that these models move into the “painterly” phase. Conversely, Wölfflin’s view of the painterly occupying a more advanced stage than the linear seems to imply the idea that the subjective infusion of life into matter — which, undeniably, is also made up of paint, plastic, or apparent information — is an artistic process. Whether the creation is epidermalized or not, the artist is searching for a balance between the subjective vitality of the human being and materiality, between “what appears in front of the eyes” and “what there really is,” in order to find the right distance for viewing.

The form of animals matches this balance. In his book The Golden Bough, James George Frazer argues that, in the face of harsh and uncontrollable natural environments, our ancestors placed their souls on animals for safekeeping, and animal totem images and totem worship have since emerged. Perhaps, from the very beginning, animal images, though symbols of nature, have always been given strong subjective colors. Today, with highly sophisticated and developed image-making technology, artists still display animal forms to hang up new skins as cognitive feedback to the natural world. But we cannot say that the new look is a denial of the inexhaustible mystery of the natural world in favor of a state of “representing what there really is.” Quite the opposite, in fact — in the exhibition, whether wild (fauvist?) tendencies are displayed implicitly or pointedly (such as in Natalie Djurberg and Hans Berg’s Delights of an Undirected Mind), the artists seem to tacitly acknowledge that the projection of their will towards the animal figure is a step into the unknown. While acts of vigor are relegated to the world of human consciousness, animal beings reside the unfathomable material world. Penetrating towering barriers is one of the sources motivating artistic creation.

The Eastern Han Dynasty scholar Gao You states in his commentary to the Annals of Lü Buwei—Almanac for the Third Month of Winter: “The day before the waxing year, drums are beaten to drive away the plague. This is called the expulsion.” In the end, even if the natural world does not entirely cater to our will, we wish that the exhibition, like the sounds of the drums, can resign the old and welcome the new. To have auspicious beasts ring in the New Spring is certainly a sign of good fortune.

1.Heinrich Wöfflin, Principles of Art History: The Problem of the Development of Style in Early Modern Art, trans. Jonathan Blower (Los Angeles: Getty Publications, 2015), 102.

2.Even though Wöfflin writes: “In his treatise on painting, Leonardo repeatedly warns painters not to outline forms,” he considers Da Vinci’s paintings to be linear depiction. Ibid., 123.

3.The notion of the beast called Nián (meaning “year”), which is widely known in folk contexts, is not found in any classical textual records. The weak spots of the beast Nián, namely its fear of loud sounds and burning fire, probably originated from the descriptions of using firecrackers to expel mandrills. Zong Lin from the Liang period of the Southern and Northern dynasties wrote in the Record of the Year and Seasons of Jing-Chu: “the first day of the first month, is the day of the three yuan. The annals calls it duan ri (the day at the very beginning of the eight solar terms). One gets up at the rooster’s crow and light firecrackers in front of the courtyard, to ward off mandrills and evil spirits.” A similar account is found in The Book of Divine Marvels. The image of the mandrill is likely the prototype of the so-called beast Nián, but this can only be verified through more in-depth examination.

Curatorial Consultant

Yang Zi, an independent curator, graduated from the Department of Philosophy and Religion of Nanjing University. He was selected as a research fellow for the first Sigg Fellowship for China Art Research in 2020 and also served as a jury member for Gallery Weekend Beijing. He was a preliminary jury member for the annual Huayu Youth Award in in 2019 and 2021. He was shortlisted for the annual Hyundai Blue Prize in 2017 and edited for LEAP in 2011. With nearly ten years of experience in art criticism and curating, Yang has curated a number of exhibitions and public programs, including the group shows The New Normal: China, Art, and 2017, Pity Party, Land of the Lustrous, In Younger Days, Decoration as well as many solo exhibitions.